With the … let’s just call it “excitement” … of the 2024 election now in the rearview mirror, it’s time to consider what comes next. Political swings are often accompanied by uncertainty, sometimes even chaos. Charitable giving is voluntary behavior, and in the face of uncertainty and chaos the rational choice is to postpone voluntary decisions like whether to make a charitable gift. The savvy planned giving officer will pivot to reinforce the reasons for giving. As tempting as it is to fret over politics, tax policy, the economy, and the stock market, we really have no control over these factors. Instead, this is an opportunity to focus on the mission, explain the community’s needs have not changed, and help our donors understand the difference they can make with their next charitable contribution.

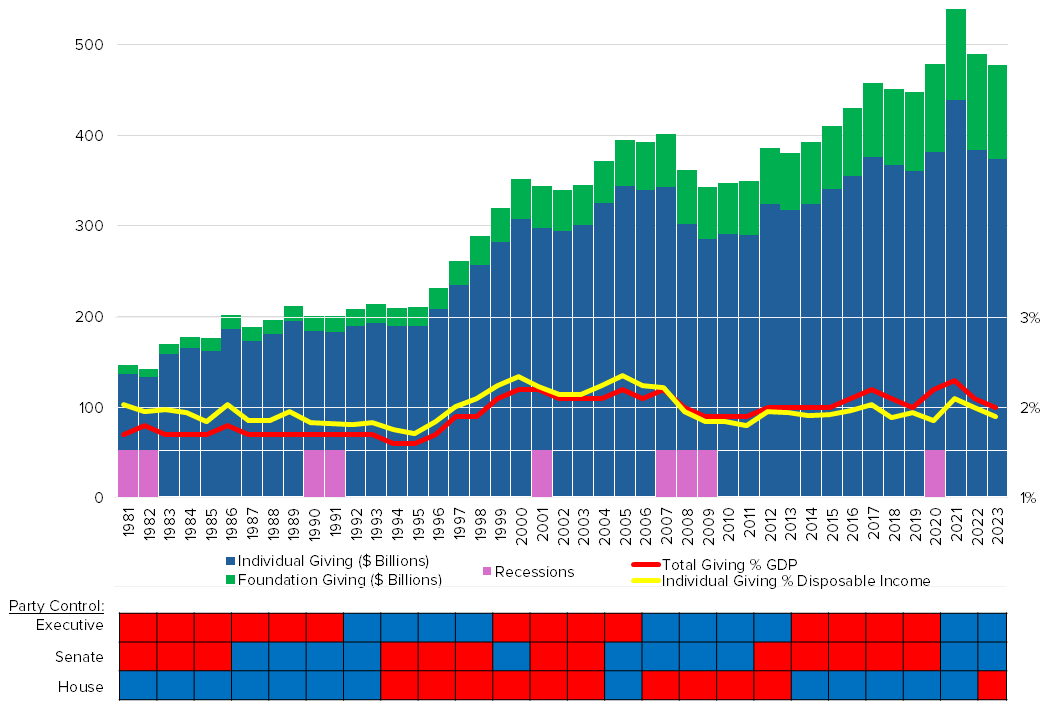

Still, it is worthwhile to review the impact of past changes in the balance of political power on overall charitable giving. The chart below shows yearly total giving (in 2023 dollars) from individuals and foundations beginning with the first year of the Reagan administration in 1980 through the third year of the Biden administration in 2023 along with the balance of power in Congress, which changes every two years, as well as total giving as a percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP – a measure of the total economy) and individual giving as a percent of Disposable Net Income.

In general, there is little apparent correlation between the dominant political party and changes in charitable giving, although there is a tendency for giving to be relatively flat during Republican presidencies and to trend upward during Democratic presidencies. When considering the balance of power in Congress, the picture is even murkier.

It is notable that giving both as a percent of GDP and Disposable Net Income have been trending downward since reaching peaks during both the Clinton and Bush administrations. The data show that charitable giving as a share of either the economy or income has not increased over the past two decades. In fact, by this measure, giving has trended downward despite increased investment in fundraising during the period. Nevertheless, the strongest correlation appears to be economic recessions, which tend to be followed by periods of slow growth in giving, as in the recessions during the Reagan and the first Bush administrations, or even declines following the Great Recession during the second Bush administration and the first year of the Obama administration.

Indeed, the data confirm the old cliche, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Nevertheless, the new administration arrives having made campaign promises regarding tax policy and changes in tax law that can create new and different opportunities for charitable giving. Planned giving officers will need to watch carefully and be prepared to react strategically to fluctuating circumstances. What concerns might surface among donors? Could potential changes affect donors’ gift plans? Anticipating donors’ qualms, we will highlight a few of the concerns likely to be on donors’ minds with respect to charitable giving.

Almost certainly, the highest tax policy priority for the new administration will be extending the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), which will expire at the end of 2025 unless Congress acts. The outcome is highly uncertain in part because preserving much of TCJA will be very expensive, and tax legislation generally must be revenue neutral, i.e. extending the TCJA tax cuts would need to be balanced with off-setting budget reductions.

Here are four specific elements of TCJA and how they may affect donors’ inclination to give:

- Income Tax – If TCJA is not extended, the previous income tax brackets, including the 39.6% top tax rate, will be restored beginning in 2026. This would increase income taxes for many taxpayers – especially those with higher incomes. Donors may be inclined to curtail their giving if they become concerned about an increase in their income tax bill. Conversely, higher income tax rates would have the positive effect of increasing the value of the charitable deduction and, therefore, reducing the donor’s after-tax cost of giving. A careful explanation of the income tax savings and after-tax cost of giving could encourage donors.

- Standard Deduction – Prior to TCJA, about one-third of taxpayers itemized their income tax deductions, but after TCJA doubled the standard deduction, only about 10% of taxpayers itemize – and non-itemizers cannot take advantage of the charitable deduction. Unless Congress acts, the Standard Deduction amount will decrease in 2026, and significantly more potential donors will be able to claim a charitable deduction. If an extension of the Standard Deduction appears to be off the table, some donors may decide to postpone their charitable giving until 2026 when they may be able to take full advantage of itemizing their deductions.

- Capital Gains Tax – One way for Congress to pay for an extension of TCJA would be to adjust the capital gains tax. There are few specific proposals, but if long-term capital gains become more highly taxed, the advantages of a charitable contribution of appreciated property would increase. Gifts of long-term appreciated assets provide a double tax benefit: a charitable deduction for the fair market value of the asset and avoidance of the capital gain tax that would have been due if the asset had been sold. Suggesting contributions of highly appreciated assets and pointing out the tax advantages could help donors overcome reluctance to consider a contribution. And remember, even non-itemizers can avoid capital gains tax by contributing appreciated property.

- Estate Tax – TCJA essentially doubled the estate tax exemption (the “tax-free” amount), but, like many other provisions, this will revert to pre-TCJA levels unless Congress acts. From a populist perspective, allowing the restoration of the pre-TCJA threshold may be the least unpopular change because the estate tax currently affects fewer than 0.5% of estates and would still affect only about 2% of estates even if the pre-TCJA exemption is restored. Reminding donors that there is an unlimited charitable deduction that reduces the estate tax and showing them the substantial income tax and estate tax benefits of testamentary contributions of qualified retirement plans would be in order. For certain select donors, a conversation about the gift and estate tax savings and other benefits of charitable lead trusts could be productive.

Whatever the future may bring, we know that donors are motivated to give by their passion for the organization’s mission. Even if political events and news about legislative initiatives discourage some donors, good gift planning can help maintain and even increase the quality and quantity of their giving.

A Brief Civics Review

Anticipating donor anxiety, an understanding of the legislative and political processes that are likely to play out over the coming months may be helpful. It is not possible in this short article to provide a comprehensive civics lesson, but a review of the fundamental structure of the Federal government and certain legislative processes can provide helpful background or perhaps fill in gaps in our own knowledge when navigating conversations with donors.

Executive Versus Legislative

The President heads the Executive Branch of the Federal government and is charged with carrying out the laws that are enacted by Congress, the Legislative Branch. The span of the Executive Branch is very broad, encompassing the departments and administrative functions of the Federal government, including the Treasury Department where the Internal Revenue Service resides. However, the power of the executive is limited. With few exceptions (see Executive Orders below), the President cannot act unilaterally. Ultimately, the executive functions report to the President, but their power is limited by the laws enacted by Congress. For instance, although the Internal Revenue Service issues regulations and other guidance for interpreting and implementing the Federal tax laws, it is bound by the Internal Revenue Code, which is written by Congress.

The House and the Senate

Congress consists of 535 elected individuals divided into two bodies, the House of Representatives and the Senate. The 435 members of the House of Representatives are apportioned based upon population with each House member representing about 750,000 people. House members serve for just two years before they must run for re-election. Two Senators represent each state, serving for six years with their terms staggered so that approximately one-third of the Senators stand for election every two years.

119th Congress

A Congress lasts for two years. The 119th Congress will begin in January 2025, and will conclude at the end of 2026. Each Congress starts with a blank agenda; nothing is carried forward from the previous Congress. Proposed legislation that is not acted upon before the end of the current Congress (the 118th) becomes void and will need to begin the legislative process again in the 119th Congress.

Congressional Leadership

The Speaker of the House heads the House of Representatives and is elected by its members. In January 2025, the members of the House of Representatives will elect the next Speaker of the House, and the Senators will elect the Senate Majority Leader. Because these elections are a simple majority vote, the Speaker and the Senate Majority Leader will almost certainly represent the political party holding a majority in each chamber. The Speaker of the House and the Senate Majority Leader set the agendas and manage the affairs of their respective bodies including, most importantly, determining if and when proposed legislation is considered by the body. (The Vice President of the United States serves as the President of the Senate but casts a vote only in case of a tie and rarely attends Senate sessions.)

Congressional Committees

Much of the work of Congress is accomplished in its committees. Committee membership is assigned by the two political parties and is roughly equal to the balance of seats held by each party. Because the majorities in each chamber are so narrow, committee membership is likely to be more or less evenly balanced. However, Committee chairs are selected by the majority party, and the Committee Chair sets the committee agenda, which means that the majority party wields significant power over the committees.

House and Senate Rules

During the first few days of the 119th Congress, each chamber will adopt its own rules governing how the body will operate, including how much time is allotted for debate before a vote must be taken (see Filibuster and Cloture below). These rules are voluminous and usually are simply rolled over from one Congress to the next. However, anything can happen. Under certain circumstances, a rule can be set aside or amended, but this usually requires a super majority vote of the body.

Filibuster and Cloture

Although not a part of the Constitution, a “filibuster” is an attempt by a member to hold the floor in order to prevent a vote, thus blocking a legislative action. The filibuster is rare in the House because its rules have traditionally imposed limitations on the length of debate. Filibusters are more common in the Senate where there have been fewer limitations on debate. However, a Senate filibuster can be halted if 3/5ths (60) of the Senators vote in favor of a “cloture” motion to end debate. As a practical matter, Senators rarely take to the floor and hold forth in an actual filibuster. Instead, when a Senator notifies leadership of the intention to filibuster, leadership moves on to other business unless it is confident it can muster 60 votes in favor of cloture. The practical effect is that most legislation in the Senate requires a 60-vote margin. The Senate has changed its filibuster rules over the years (see Budget Reconciliation below), most recently in 2017 when the cloture threshold was reduced to a simple majority to end filibusters of Supreme Court nominees.

Budget Reconciliation Bill

Reconciliation is a rule that can be applied to prevent a filibuster of certain budgetary legislation. Reconciliation Bills can involve spending, revenue, or the Federal debt limit, and there can be only one Reconciliation Bill for each of these subjects each year (a potential total of three Reconciliation Bills per year). The “Byrd Rule” prohibits Reconciliation Bills from including policy changes that are extraneous to the budget, increase the Federal deficit after a ten-year period, or make changes to Social Security. Reconciliation Bills have been used several times in recent years, including the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which allowed it to pass with bare majorities on near party-line votes. (Note: The reason many of the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 expire at the end of 2025 is to comply with the ten-year budget neutral requirement.) Nevertheless, Reconciliation could be used by Congress to enact certain tax policy changes without the need for 60 votes in the Senate (see Filibuster above).

Making a Law

A bill must be drafted, introduced, debated, and passed in identical form by each chamber before it is sent to the President for signature. If the President refuses to sign the legislation, Congress can override the President’s veto by a 2/3rds vote in both chambers. In most cases, leadership refers a bill to a committee for review and recommendation. Committees may hold hearings, order studies, make changes to the proposed legislation, or simply do nothing. After a committee refers a bill to the body, leadership controls when or if the matter is brought to the floor for action. In most cases, members can propose amendments to the bill during debate on the floor.

Executive Orders

The President can issue Executive Orders covering many operations of the Federal government, but there are limitations. Although the Constitution gives the President broad executive and enforcement authority and Congress has delegated certain discretionary power to the President, an Executive Order is not a substitute for legislation. Executive Orders are subject to judicial review and can be overturned if the Court finds that the order lacks support by statute or the Constitution. Executive Orders remain in force until canceled. Typically, a new president reviews existing Executive Orders during the first few weeks in office. It is expected that President Trump will review and cancel some of the Executive Orders issued by President Biden. It is also possible that President Trump may enact certain tariffs by Executive Order.